How the Belle Époque Invented the Art of Being Seen

She walked through the salons of the Faubourg and the foyers of the Opéra, under chandeliers and gloved hands. Her waist was sculpted, her face powdered to an impossible whiteness, her gaze perfectly composed. The newspapers had a name for her: the professional beauty.

The phrase, circulating through the fin-de-siècle press, meant more than mere attractiveness. It described a woman who had made a vocation of appearance — too perfect to be natural, too controlled to be innocent. In a world learning to live through images, she was both symptom and pioneer: the woman who understood that beauty could be a profession.

A society of appearances

At the turn of the century, Paris entered a new regime of visibility. Illustrated magazines, studio photography, and the expanding culture of advertising reshaped the way people perceived themselves. Beauty was no longer a gift; it was a skill. One could study it, practice it, refine it. Manuals of etiquette gave way to guides on posture, complexion, and lighting. The art of being looked at became a form of social competence.

A new economy of expertise emerged around this ideal. Hairdressers, couturiers, perfumers, and photographers joined forces to manufacture an aesthetic of control. The face and the body became surfaces of discipline — maintained, adjusted, trained. Beauty turned technical.

It was, in a way, a quiet revolution. To be beautiful was no longer to be something, but to do something. And that shift — from essence to practice — disturbed the moral imagination of the Belle Époque. A woman who managed her appearance too consciously was no longer simply admired; she was suspected of professionalism.

Madame X and the scandal of self-awareness

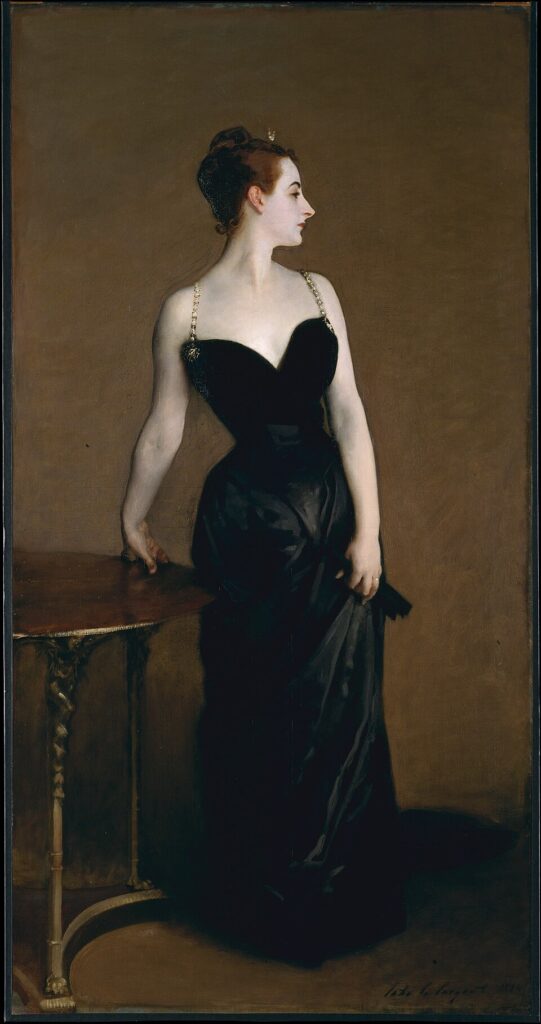

In 1884, John Singer Sargent unveiled at the Paris Salon what he thought would be his masterpiece: the portrait now known as Madame X. The sitter, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, an American expatriate celebrated for her alabaster complexion, was the epitome of the modern Parisienne. Sargent portrayed her in a black gown, the strap of one shoulder daringly slipping down her arm. Her skin gleamed like porcelain; her pose was statuesque, calculated, almost defiant.

The reaction was immediate and brutal. Critics called it indecent, lifeless, arrogant. What truly offended them was not the flesh but the consciousness of it. Madame X looked as though she knew exactly what she was doing. She appeared complicit in her own representation, almost co-author of the image.

In that small gesture — the deliberate poise, the fallen strap — the public sensed a threat. The woman had become an active participant in her own depiction. The professional beauty had entered the frame, and Paris was not ready to look her in the eye.

Sargent had to remove the sitter’s name, repaint the strap, and leave France for London. But the portrait survived as an emblem of a changing world: a world where the control of appearance was beginning to rival the authority of art itself.

The beauty industry before the name existed

While the scandal echoed through the salons, the machinery of beauty was becoming a profession in the literal sense. Around 1900, Paris was covered with beauty institutes, photographic studios, couture houses, and perfumeries. The body was increasingly a site of expertise — medical, commercial, aesthetic.

Cosmetics were advertised as scientific, powders as hygienic, perfumes as therapeutic. The language of chemistry replaced that of grace. The modern woman, armed with products and knowledge, was invited to “improve” herself, not to conceal but to optimize.

A professional beauty was not necessarily an actress or courtesan. She might be a society woman who followed the latest formulas, ordered from Worth or Poiret, posed for Reutlinger, and knew exactly how much light her skin could bear. Her beauty was learned, not bestowed. That, precisely, was her crime and her triumph.

Writers like Zola and Maupassant captured this new type with a mixture of fascination and irony — women whose elegance seemed engineered, whose allure was indistinguishable from their intelligence. The professional beauty was both product and producer, a self-made image in a culture obsessed with surfaces.

A new chain of artisans

The term also applied to those who shaped these women. Hairdressers, couturiers, manicurists, photographers — each contributed to the fabrication of visibility. Their work formed a discreet chain of artisans, transforming flesh into representation.

In their studios, beauty was treated as a craft with measurable outcomes: proportions, balance, the angle of a jawline under artificial light. Manuals spoke of “scientific methods of beauty.” Early courses in applied aesthetics appeared; products were marketed as medical instruments.

This rationalization marked the passage from moral to technical beauty. The body was no longer a moral sign but a professional object — something that could be improved, standardized, even mass-produced. The natural became procedural. The private became public.

Distinction and confusion

Such professionalization blurred the lines of class. For centuries, social distinction had depended on birth, manners, and restraint. The Belle Époque replaced that with visibility. A well-dressed actress could outshine a duchess; a fashionable courtesan could dictate taste to the bourgeoisie.

Beauty became a currency — a portable form of capital. The ability to manage one’s appearance offered mobility in a society otherwise rigidly stratified.

Figures like Cléo de Mérode, Lina Cavalieri, and Sarah Bernhardt embodied this new order. They controlled their portraits, negotiated their image rights, and understood the economics of celebrity. They were, in every sense, professional beauties — both subject and object, both brand and body.

For moralists, this was deeply unsettling. The professional beauty was accused of artificiality, manipulation, vanity — in short, of knowing too much. Behind the aesthetic reproach lurked a social anxiety: a woman in control of her image was a woman no longer under control.

The male gaze, confused

The commentary surrounding these women was almost entirely male. Critics and novelists wrote about them with a blend of reverence and fear. The natural beauty still belonged to the domestic ideal; the professional beauty belonged to the public sphere, and therefore to suspicion.

She was admired as a muse, mocked as a coquette, celebrated in prose and condemned in gossip columns. The contradiction said less about her than about the men who described her. She revealed the blind spot of the era: the unease with women who turned visibility into agency.

To know how to be seen was a form of power, quiet but real. Beneath the rhetoric of scandal, the professional beauty was already practicing a form of self-sovereignty — the politics of presentation.

The invention of photogenic beauty

Photography amplified this transformation. Studios like Reutlinger, Nadar, and Walery codified the grammar of the pose: the tilted head, the half-turned shoulder, the soft light on powdered skin. These portraits circulated on postcards, in illustrated magazines, and soon in advertising.

Photogenic beauty replaced expressive beauty. It wasn’t about emotion but about calibration: how the light met the face, how shadows sculpted the body. Types replaced individuals — the ethereal blonde, the tragic brunette, the mysterious redhead. Standardization and myth coexisted.

Yet within that rigidity, each sitter developed her own inflection. The art of being photogenic was to remain singular within the formula — a tension that still defines fashion photography today. To be a professional beauty was to perform individuality inside convention, to manage the illusion of spontaneity with absolute control.

The irony of progress

The Belle Époque liked to imagine itself as an age of natural charm, but it was in fact an age of procedures. Science entered the dressing room. Beauty creams promised “rational improvement,” electric treatments claimed to stimulate the skin, and the use of mild arsenic for whitening was considered perfectly respectable.

Each invention brought the ideal of perfection closer — and with it, a new unease. The more beauty became scientific, the more it seemed artificial. The more controllable it appeared, the less mysterious it felt. The professional beauty stood at that intersection: a triumph of self-management, haunted by the suspicion that mastery kills desire.

That irony is the heart of the Belle Époque aesthetic. Under the powder and the perfume, one finds the same paradox that defines modern life: the longing for authenticity through ever more elaborate artifice.

Beauty as independence

There was, however, another side to this professionalism — one less visible but no less transformative. The beauty industry opened new paths of economic independence for women. Modistes, hairdressers, manicurists, seamstresses, masseuses — all built careers from the demand for refinement.

The first schools of beauty appeared; diplomas and professional associations followed. Beauty became a legitimate trade. Entrepreneurs like Helena Rubinstein and Eugénie Schueller (founder of L’Oréal) understood that cosmetics were not frivolous but emancipatory: they allowed women to control both their appearance and their income.

Thus the phrase professional beauty shifted meaning. It no longer referred only to the woman who embodied beauty but to the one who produced it. The industry and the image grew together, each legitimizing the other.

The ghost of Madame X

Looking back, the outcry over Madame X seems almost comically moralistic. What scandalized the 1884 Salon was not a bare shoulder but a self-possessed woman. Her poise revealed that beauty could think, that the image could look back.

That, perhaps, was the real provocation: a female subject aware of the mechanism of vision. The professional beauty was not content to be admired; she participated in the making of admiration. She was the modern world’s first mirror held deliberately toward itself.

The unease persists. From film stars to influencers, the same ambivalence remains: fascination with women who perfect their image, resentment of their competence. Each new medium — cinema, television, Instagram — simply updates the formula. The professional beauty of the Belle Époque has gone digital, but her smile still knows exactly what it’s doing.

The sincerity of artifice

It is easy to dismiss this tradition as superficial, but that would miss its subtlety. The professional beauty was not the enemy of truth; she was its modern interpreter. In a society built on appearances, sincerity depends on the quality of the performance.

To master one’s image is not to lie, but to navigate a world where visibility equals existence. The art of seeming sincere — of making the artificial feel authentic — is not hypocrisy but literacy.

The women of the Belle Époque understood that long before we did. Beneath the powders and corsets, they were composing a language of self-presentation that still defines contemporary culture. Their irony was gentle but sharp: they knew that control was the only form of freedom available to them.

Madame X, with her perfect posture and fallen strap, remains their emblem — serene, strategic, and ever so slightly amused.

Read more :

✔︎ Mina Loy: The Modernist Rebel Who Rewrote the Rules

✔︎ Misia Sert: The Secret Queen of Belle Époque Paris

✔︎ The Last Summer: Picasso, Lee Miller, and a Surrealist Paradise on the Brink of War

✔︎ Teresa Wilms Montt: A Voice of Rebellion in the Dark Night

✔︎ Bonnard’s Muse: The Hidden Truth Behind Art’s Greatest Deception

15 Capsules — “Professional Beauty” (Belle Époque)

Professional Beauty — Belle Époque Capsules

Fifteen quick takes (with sources) on how Belle Époque Paris turned beauty into a profession — from Sargent’s Madame X to institutes, couture, and photogenic standards.

01 · The Strap Heard ’Round the Salon

In 1884, a single slipped strap turned a poised portrait into a moral panic. Paris wasn’t shocked by skin; it was shocked by a sitter who looked fully aware of being looked at.

02 · Beauty, Upgraded to a Verb

At the fin de siècle, beauty stopped being a state and became a practice. You didn’t “have” beauty; you did beauty — with posture, powder, lighting, and logistics.

03 · The Studio: Factory of Faces

Reutlinger, Nadar & Co. taught Paris the grammar of the pose: three-quarter turn, eyes off-camera, powdered skin catching soft light. Photogenic beauty replaced expressive beauty.

04 · Institutes of Beauty (and Other Modern Temples)

“Treatment,” “hygiene,” “science of makeup”: beauty salons marketed improvement like medicine. The mirror learned to speak laboratory.

05 · Social Mobility, Now in Powder Form

When actresses rivaled duchesses, critics cried “artifice.” Translation: distinction was no longer hereditary; it was learned, lit, and well laced.

06 · Madame X: The Gaze That Gazed Back

The scandal wasn’t nudity; it was agency. A sitter who seems complicit in her own image dares to be co-author. Paris preferred its muses mute.

07 · Proust’s Gentle Knife

“Beauty is a promise of happiness; the possibility of pleasure may be the beginning of beauty.” In other words: desire professionalizes the visible.

08 · Manuals Replaced Morals

Etiquette ceded to technique: guides taught complexion for gaslight, corsets for silhouettes, poses for plates. Virtue gave way to workflow.

09 · The “Professional Beauty” Label

Used in gossip columns and contest rules, the tag separated “natural charm” from trained, market-ready allure. Flattery with a side of policing.

10 · Chemistry, Meet Vanity

Lotions, powders, even mild arsenic: the era sold “rational” beauty. Modernity promised authenticity through ever finer artifice. (Still does.)

11 · Branding Before Brands

Bernhardt, Mérode, Cavalieri curated signatures long before “personal brand” was a phrase — consistent poses, controlled prints, careful scarcity.

12 · The Satire Writes Itself

Caricatures mocked salons, institutes, and “manufactured” faces. Satire hates what threatens hierarchy; professionalism in beauty did exactly that.

13 · Madame X: Strap Repainted, Problem Remains

Sargent raised the strap; scandal stayed in the frame. You can edit fabric, not modern consciousness.

14 · The Economy of Attention (1900 Edition)

Couture staged the body; photography multiplied it; publicity priced it. Beauty became a unit you could mint, spend, and renew.

15 · Proust, Again, With Feeling

“The only true paradise is a paradise we have lost.” The Belle Époque perfected the look that would later be mourned — because it worked.

Afterthought — From Belles Professionnelles to Instagram

- Image as labor: Then: pose, powder, proof print. Now: shoot, edit, post. Same craft, faster feed.

- Intermediaries: Then: photographer, couturier, salon. Now: stylist, creator tools, algorithm. The middle keeps the gate.

- Ambivalence: Then called “artificial,” now called “fake.” Mastery of appearance still reads as threat — and sells as expertise.