At the heart of American modernist photography in the 1930s and 1940s, Edward Weston’s work stands out for its rigorous pursuit of pure form, a visual language that prioritizes clarity and objectivity. For years, the story of this intensely productive period has cast Charis Wilson almost exclusively as his emblematic muse and model. This narrative, while rooted in her frequent presence in his photographs, oversimplifies a far more complex creative dynamic. It obscures the intellectual and practical work of a partner who was an organizer, writer, and critical sounding board.

A factual analysis of their twelve years of shared life and work, from 1934 to 1946, demands a reassessment of this framework. By examining their journals, correspondence, and joint publications, it becomes possible to document the nature and extent of Wilson’s involvement. Far from a passive inspiration, she was an active agent in the creative process. This article moves beyond the myth to present the documented facts of the major artistic collaboration between Edward Weston and Charis Wilson, offering a more precise account of their mutual contributions to a foundational body of modernist photography.

Historical and Artistic Context

The 1930s were a turning point for American photography as it asserted itself as an autonomous art form. On the West Coast, a modernist movement organized in opposition to the pictorialist aesthetic, which it deemed overly sentimental and imitative of painting. This current championed “straight photography,” defined by its impeccable sharpness, scrupulous attention to detail, and rigorous composition. Edward Weston was a leader of this new approach. In 1932, he co-founded Group f/64 with Ansel Adams and Imogen Cunningham. The group’s name was itself a technical and aesthetic manifesto, referring to the smallest lens aperture, the one that provides the greatest depth of field and thus maximum sharpness across the entire image.

It was in this environment of intellectual and artistic ferment that Weston and Wilson met in 1934. California, particularly the community of Carmel where Weston lived, was a haven for artists, writers, and thinkers. This ecosystem fostered experimentation and interdisciplinary exchange. Before meeting Wilson, Weston already had an established career, marked by his pictorialist beginnings and a radical transformation in Mexico alongside Tina Modotti. His return to California coincided with the consolidation of his style. His encounter with Charis Wilson came at a moment when his visual language was mature, but his ability to execute large-scale projects required a new level of organization.

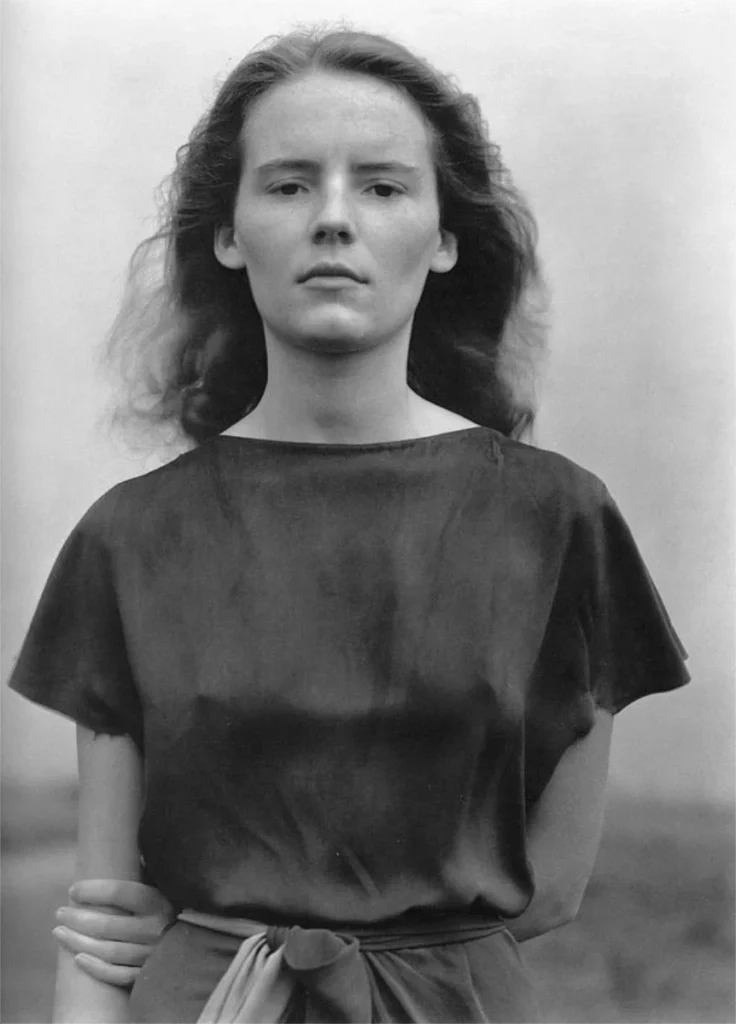

Charis Wilson: More Than a Muse

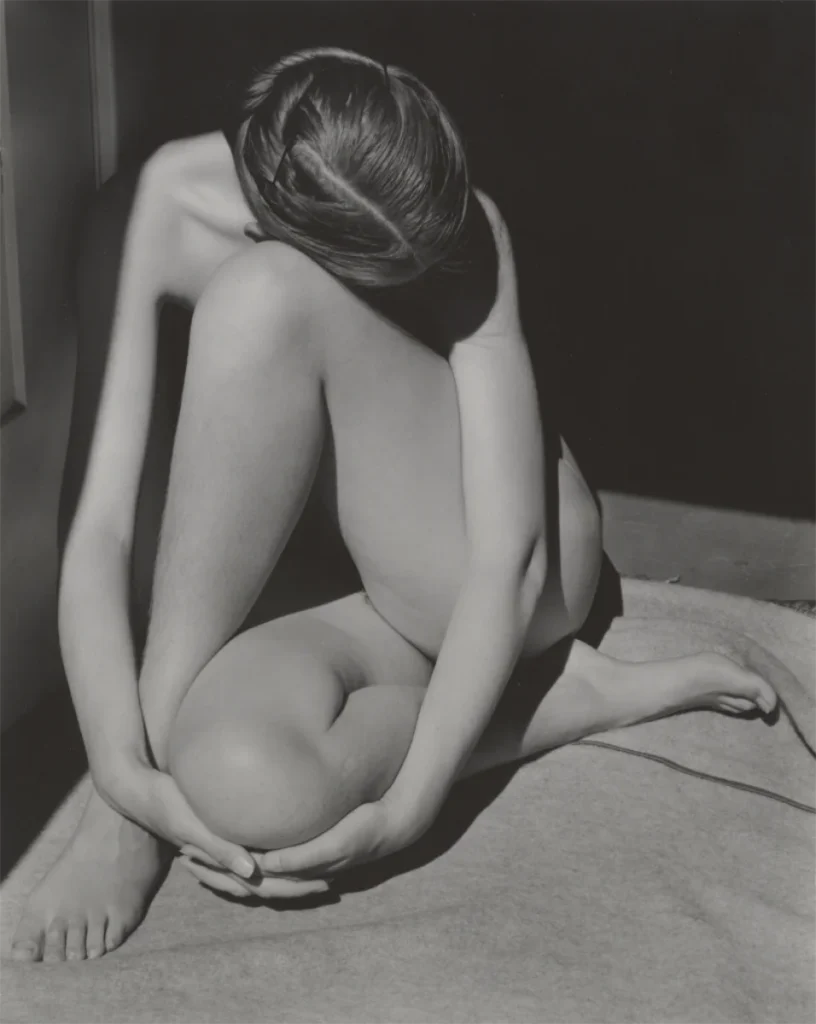

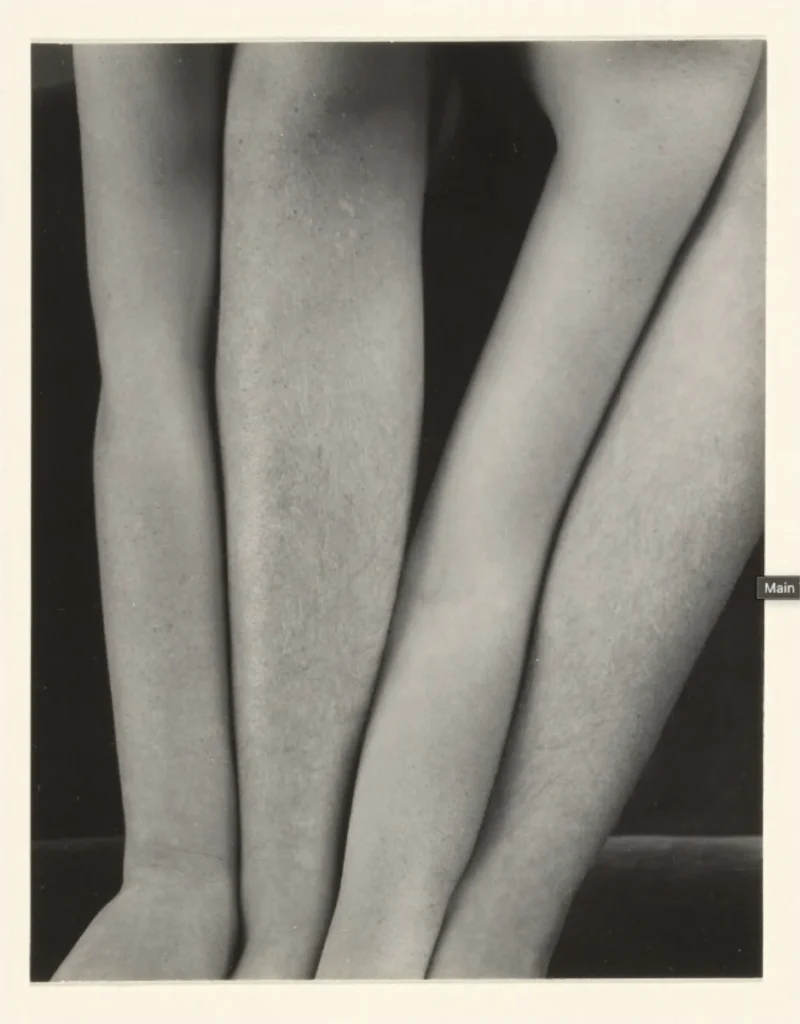

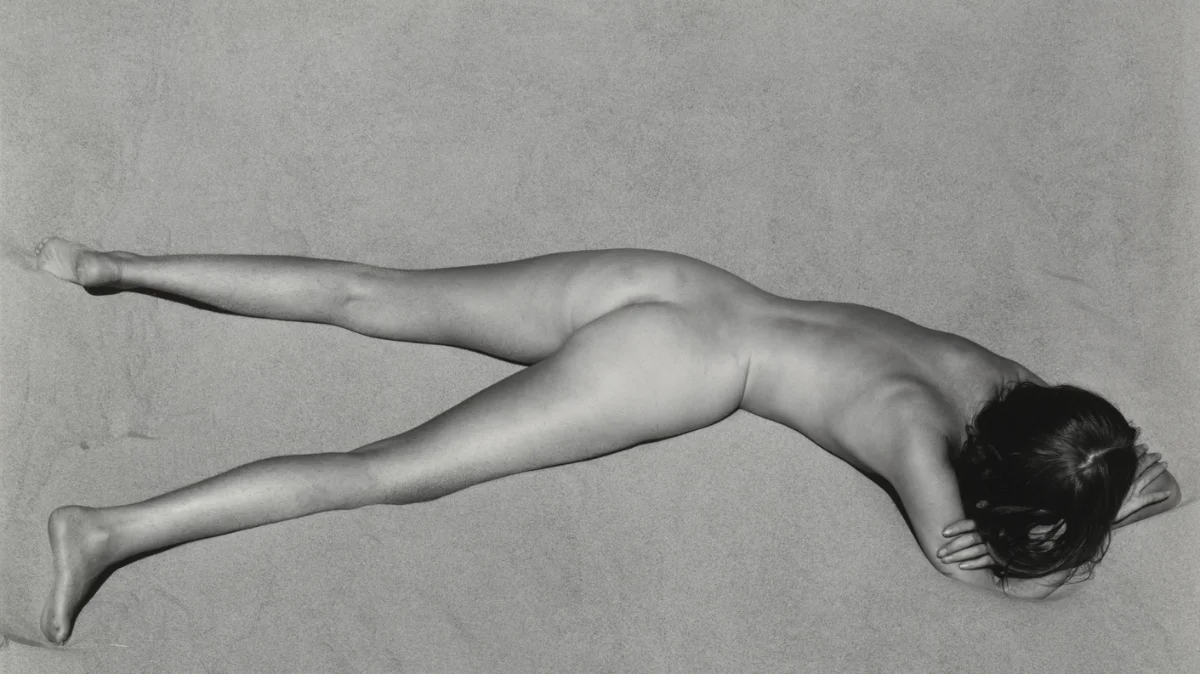

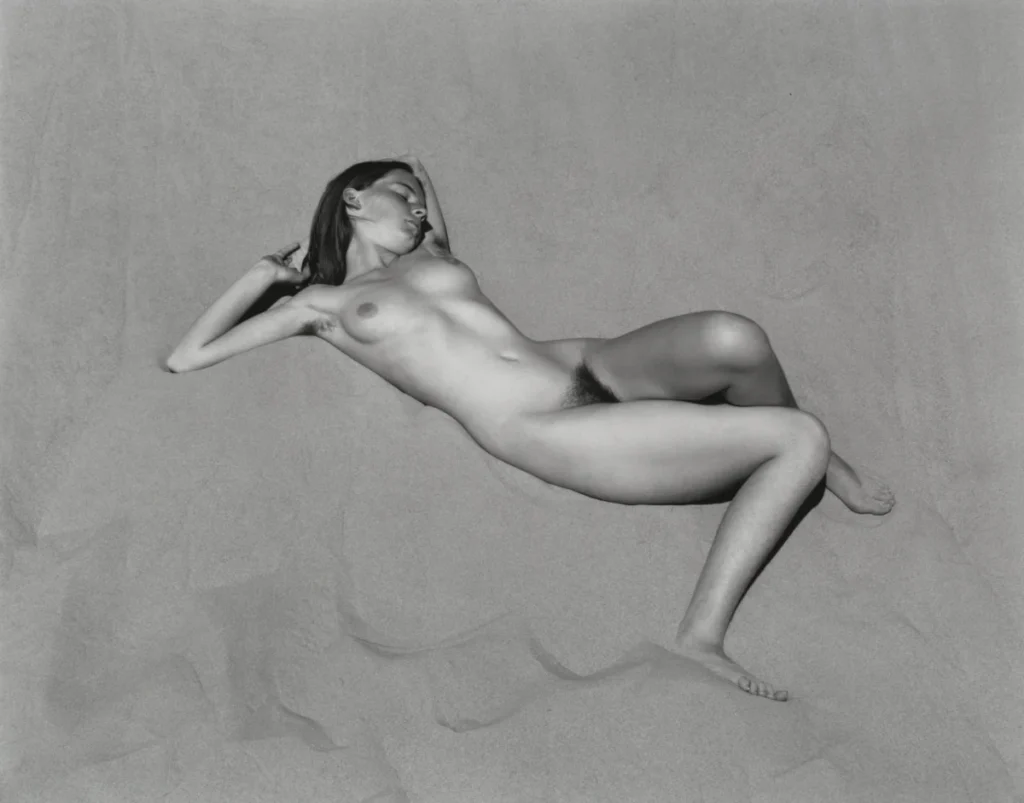

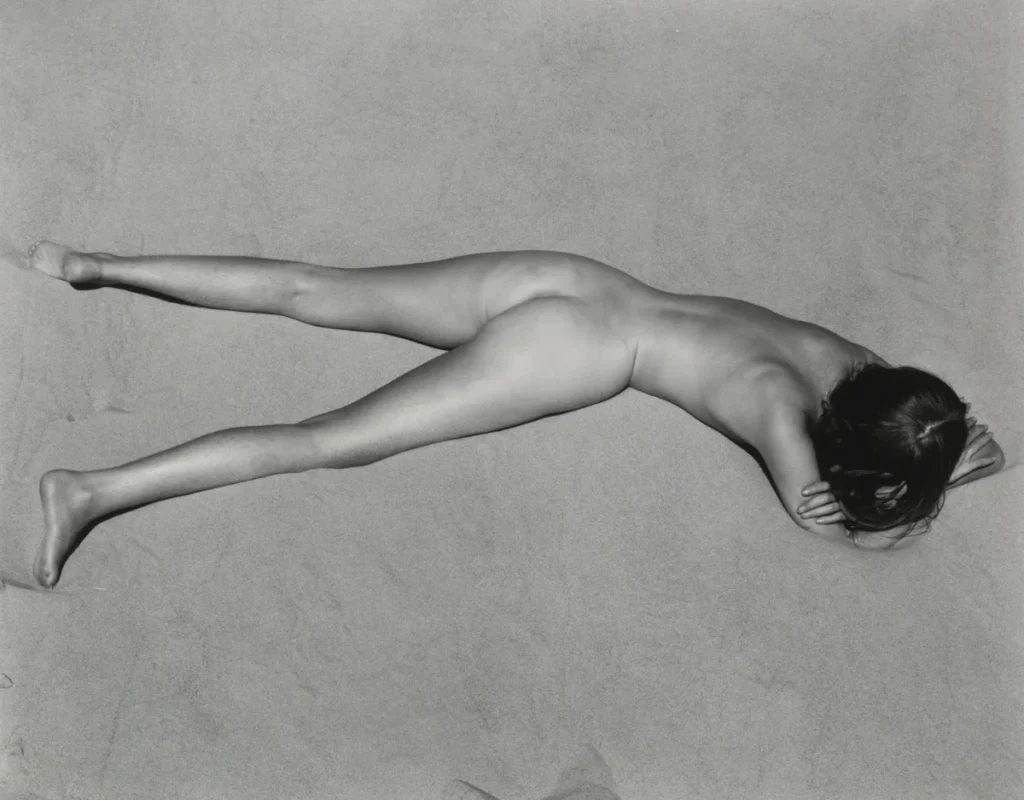

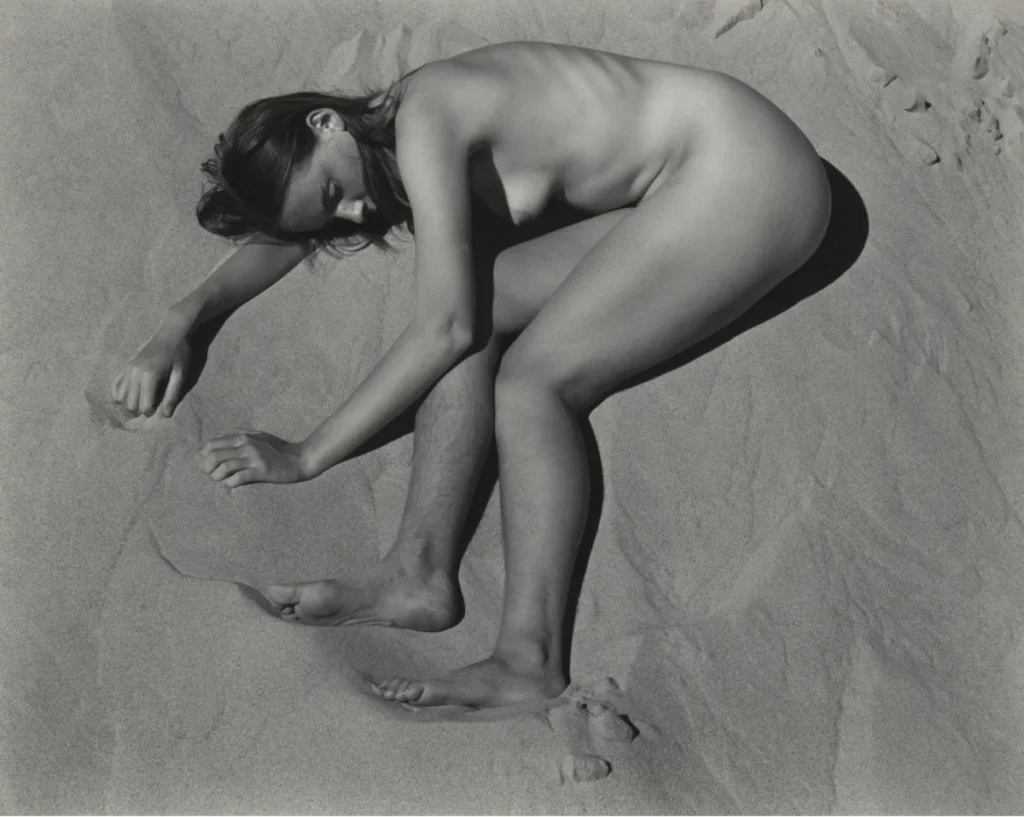

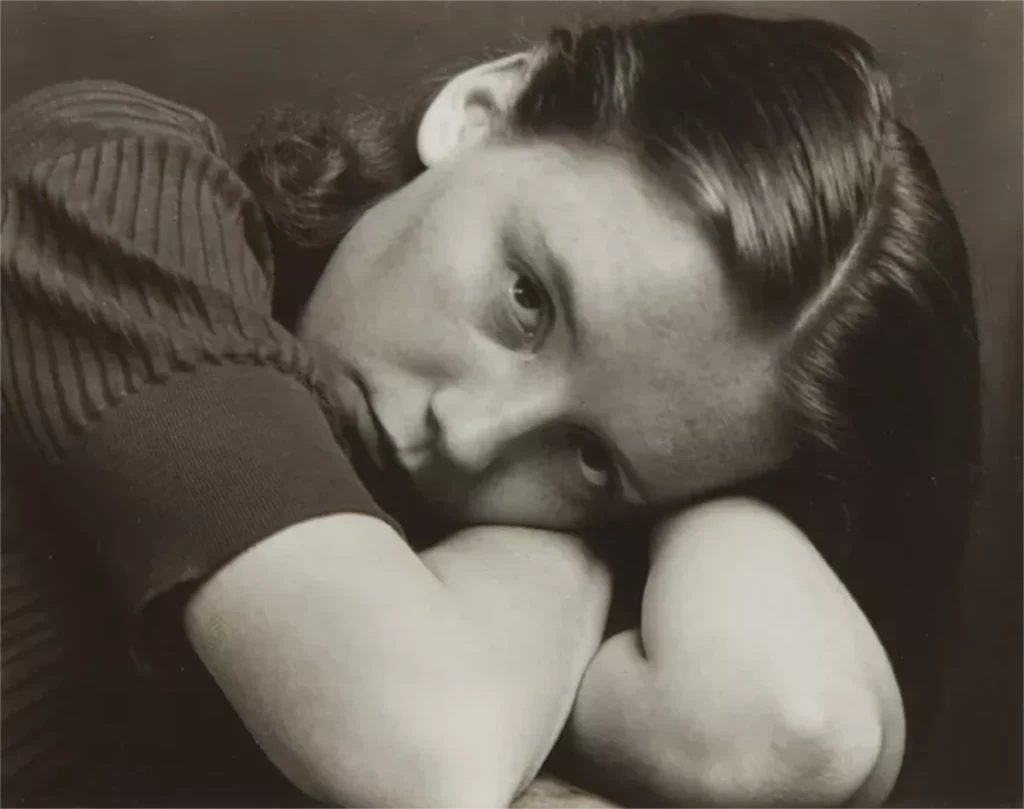

Art history has primarily remembered Charis Wilson through the images of her body, which became a subject of formal exploration under Weston’s lens. The series of photographic nudes taken on the Oceano dunes in California are among the photographer’s most celebrated works. In these images, human forms merge with landscapes, skin dialogues with sand and light, in a quasi-sculptural approach that verges on abstraction. While the power of these images is undeniable, their prominence in the narrative has eclipsed the other dimensions of Wilson’s contribution. The focus on her role as a model reinforced the myth of the muse, a passive figure whose sole function is to inspire the creative genius.

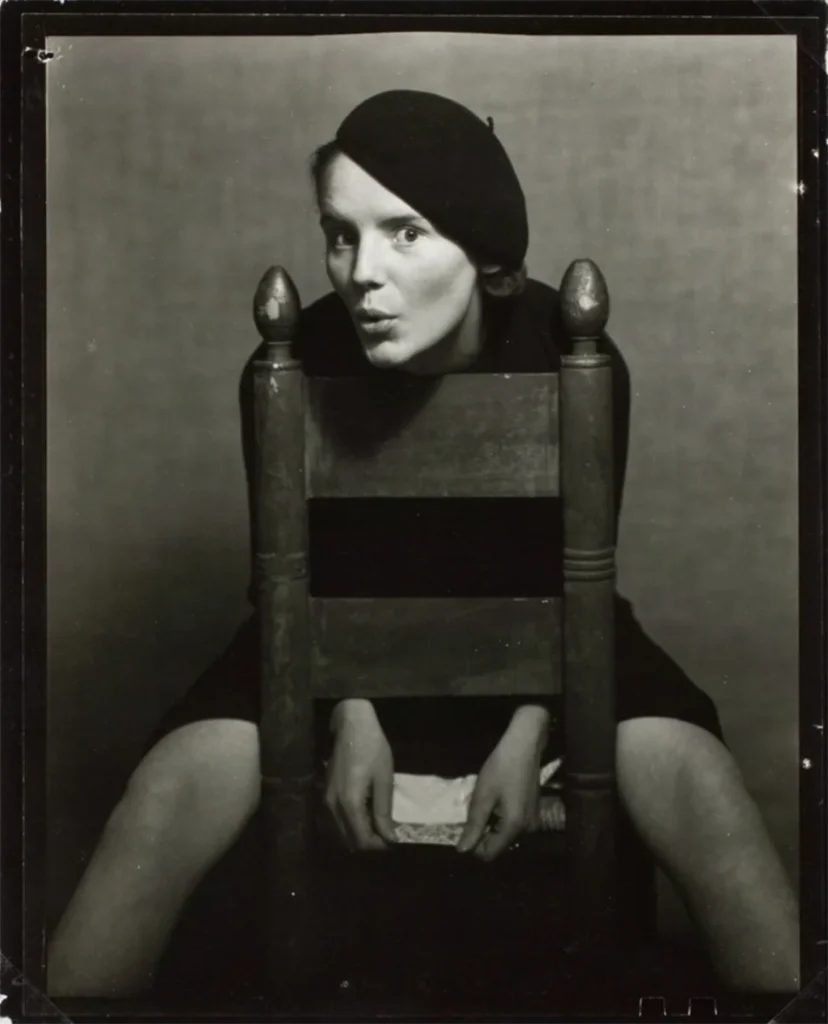

Yet, Charis Wilson’s biography reveals an intellectually sharp and active individual. The daughter of successful novelist Harry Leon Wilson, she grew up in a literary environment and held her own ambitions as a writer. From the beginning of their relationship, her involvement in Weston’s work extended far beyond modeling sessions. She quickly became his studio assistant, managing his voluminous correspondence, organizing his archives, and helping prepare his exhibitions. She also participated in editing his famous Daybooks, an essential record of the photographer’s thinking. Her critical eye and command of language made her a trusted interlocutor. This active participation in the daily work of creation profoundly challenges the historical role of women in photography. Her case is a perfect illustration of how women’s intellectual contributions have often been rendered invisible, subsumed by the figure of the male artist. The question is not whether she was a muse, but to recognize that she was a working partner.

The Guggenheim Fellowship Turning Point (1937)

In 1937, a major event confirmed the importance of this collaboration: Edward Weston was awarded a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation. This was an unprecedented institutional recognition, as he was the very first photographer to receive one. The fellowship not only validated his status as a major artist; it legitimized photography as a full-fledged art form, capable of sustaining a large-scale documentary and aesthetic project. This success was based on a four-page application, a clear and articulate text that laid out the artist’s vision. That foundational document was written entirely by Charis Wilson. Her precise and persuasive writing was decisive in the foundation’s decision.

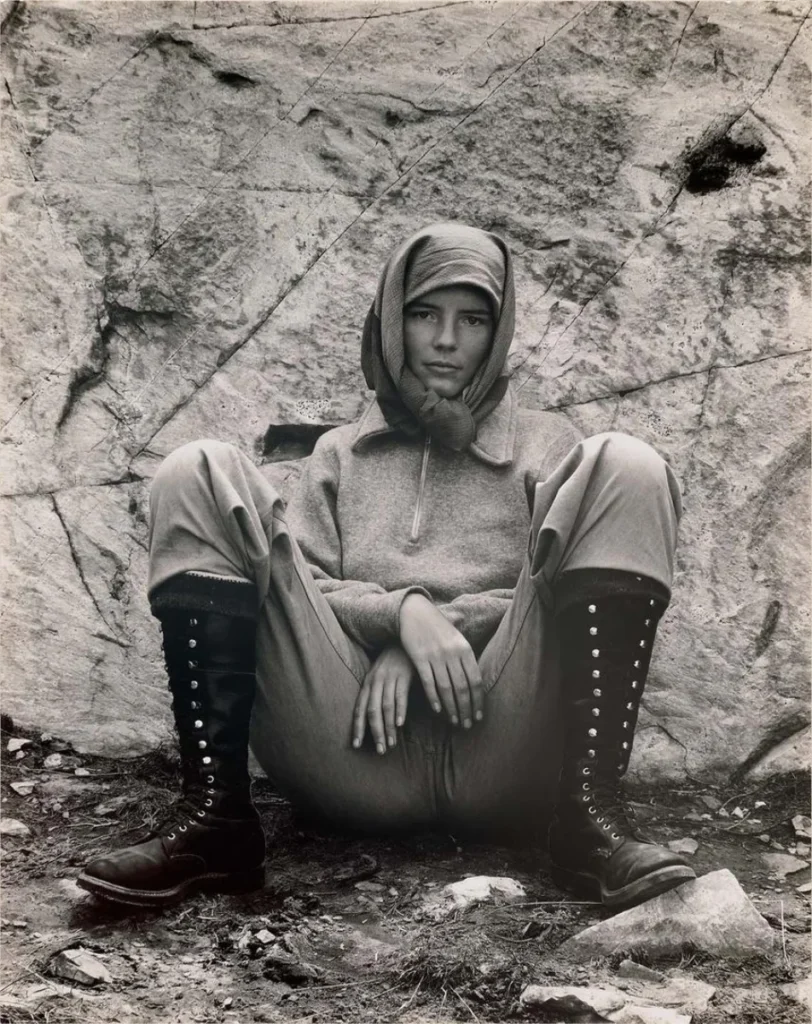

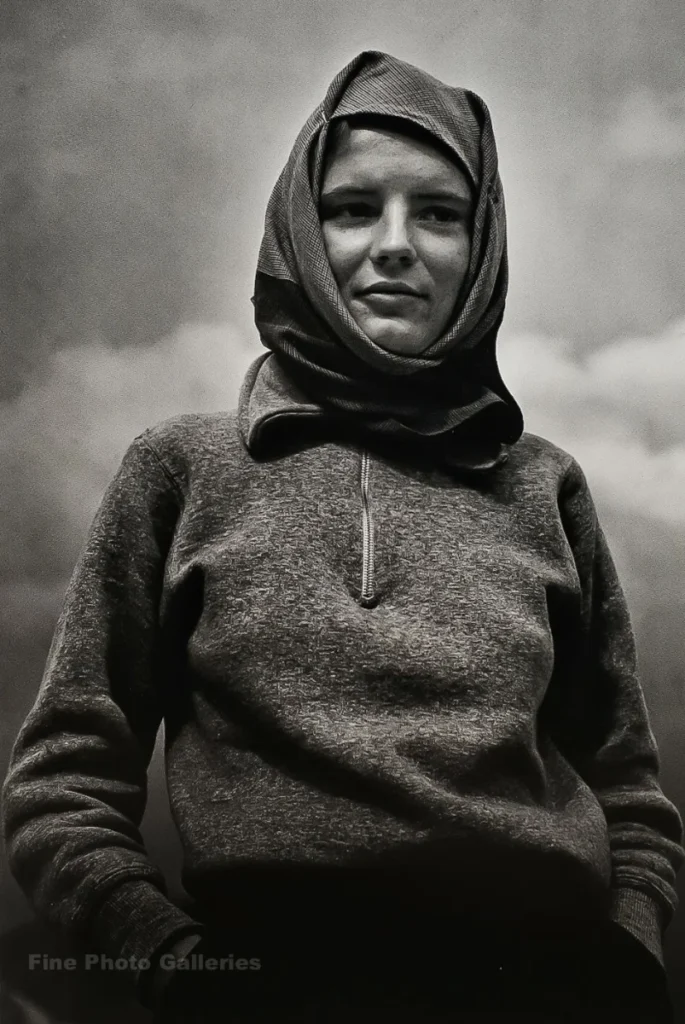

The $2,000 grant funded the Edward Weston Guggenheim trip, a project that would last nearly two years. The couple crisscrossed the American West in their Ford V8, covering tens of thousands of miles. Since Weston did not have a driver’s license, Wilson was the sole driver. But her role went far beyond logistics. She kept a meticulous logbook, recording not only the details of the journey (locations, mileage, expenses) but also observations on the landscapes, the people they met, and Weston’s working process. She became the expedition’s archivist and memorialist. This rigorous organization freed Weston from material constraints, allowing him to concentrate exclusively on making pictures. As she would later write, their partnership was based on a clear division of labor: “Edward was the image-maker and I was the word-smith.”

Aesthetics and Writing: A Creative Dialogue

Perhaps the most iconic product of this artistic collaboration is the book California and the West, published in 1940. The volume pairs a selection of photographs from the Guggenheim trip with a text written by Charis Wilson, based on her logbooks. This is not a simple book of captioned photographs. Wilson’s text is not mere captioning; it stands as an autonomous narrative, a travelogue that offers a narrative, human, and sometimes humorous context to Weston’s often austere and formal images. This dialogue between the visual and the textual is tangible proof of co-creation. Charis Wilson’s artistic writing enriches the reading of the photographs, while Weston’s images anchor the story in a specific geographical and aesthetic reality.

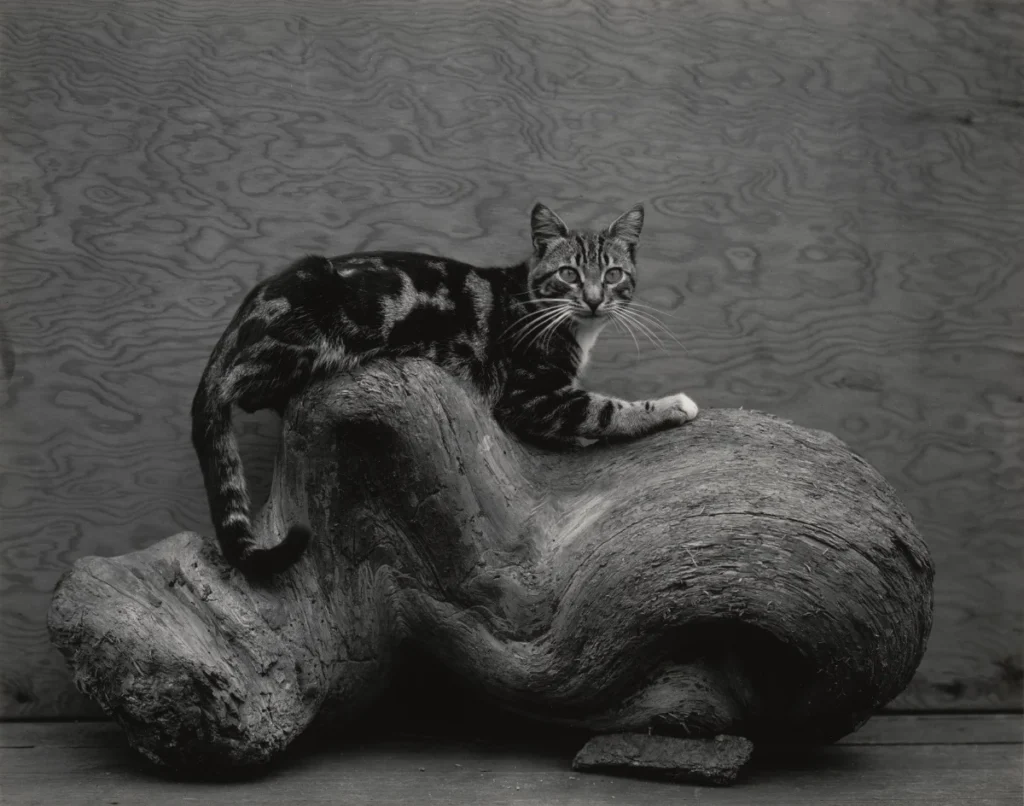

This collaborative dynamic is also evident in the creation of the artistic nudes in California. Wilson herself described the posing sessions not as a passive submission to the photographer’s eye, but as an introspective experience, akin to “meditation.” Her situational intelligence and conscious participation helped move beyond the simple relationship between artist and model. This more balanced power dynamic undoubtedly contributed to the singularity of these images, which avoid objectification by celebrating pure form. Another project, The Cats of Wildcat Hill (1947), demonstrates their ability to collaborate on a lighter subject. Weston photographed the many cats at their Carmel home, and Wilson wrote witty texts to accompany the images, once again showcasing their creative complicity.

End of the Collaboration and the Rewriting of History

The partnership between Charis Wilson and Edward Weston ended with their divorce in 1946. This separation marked the beginning of a long process of erasing Wilson’s role from the official history of Weston’s work. Several factors contributed to this. Suffering from Parkinson’s disease, Weston stopped photographing soon after their split. The preservation of his legacy was then managed by his sons, who focused on the figure of the master and father. At the same time, the historiography of modern photography, then in its formative years, tended to favor heroic narratives centered on solitary male geniuses. The romanticized artist-muse relationship in the 20th century provided a far more convenient narrative framework than the more complex one of a working partnership.

It was not until the 1980s and 1990s, with the rise of feminist art history, that Wilson’s role began to be reassessed. Critics and historians like Andy Grundberg started re-examining the archives to highlight the female influences in modern art. Recent exhibitions dedicated to the Weston-Wilson duo have presented their joint works to the public, re-establishing the material reality of their collaboration. This rediscovery of Charis Wilson is part of a broader movement to recognize women whose creative contributions were absorbed by the fame of their male partners.

A thorough examination of the relationship between Charis Wilson and Edward Weston leads to a clear conclusion: her role was not that of a simple muse, but that of an essential collaborator. Her structural contributions, both intellectual and logistical, were a necessary condition for the realization of some of Weston’s most ambitious projects, particularly during the Guggenheim period. Re-evaluating her contribution does not diminish Weston’s photographic genius, but rather offers a more accurate and complete understanding of his creative process.

Their historic artistic partnership serves as a case study for questioning the established narratives of art history. It invites us to look critically at the very notion of the “muse,” a term that has often served to mask the reality of intellectual and collaborative work. The story of the Weston-Wilson duo encourages us to search, behind other great male artistic figures of the 20th century, for the decisive contributions of partners whose names have been erased by an oversimplified telling of history. To understand their story is to recognize that creation is rarely a solitary act, but more often the result of a dialogue.